Let us treat you like royalty!

Just as Napoleon himself was hosted on Wierzbowa Street in 1812. We offer you not only a unique vodka pairing experience but also a menu that allows you to enjoy nearly the same dishes the Emperor of France savored 200 years ago. Visit Elixir with your entourage and enjoy an exceptional time with us.

Warsaw has been building its culinary culture for centuries. As the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, it experienced dynamic historical changes and was home to many nationalities. It’s no surprise that a rich culinary tradition developed, drawing inspiration from Tatar-Turkish, Ruthenian, Jewish, French, German, and Italian flavors, among others. The lavish feasts in the palaces of magnates and bishops along Krakowskie Przedmieście, Miodowa, Długa, Senatorska, and Wierzbowa streets were legendary, as were the gatherings in the merchant houses of the Old and New Towns. Meals were much simpler and more modest in taverns, inns, and pubs, but by the 18th century, stylish cafés and restaurants modeled after foreign establishments began to appear in Warsaw.

Wierzbowa Street plays an important role in Warsaw’s beautiful history. In the 17th century, the palace of the Poznań bishop Stefan Wierzbowski was built here, giving the street its name. The palace frequently changed owners, hosting families like the Radziwiłłs, Donhoffs, Sanguszkos, and Potockis, as well as Henryk Bruhl, a minister to King Augustus III. In 1797, the Prussian Hotel was established in the palace, and after a change of ownership and renovation in 1803, it was renamed the English Hotel, which also housed a renowned restaurant.

Great history entered Wierzbowa Street within the walls of the English Hotel in the person of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte in December 1812. This was the Emperor’s third visit to Warsaw. For fans of famous romances, the earlier visits are better known: in December 1806 and during the Carnival of 1807, when Bonaparte fell in love with the Polish noblewoman Maria Walewska. A little-known fact is that Madame Walewska learned French and piano from Nicolas Chopin, the father of the renowned Polish composer Fryderyk Chopin. Interestingly, Fryderyk Chopin was the same age as Alexander, Bonaparte’s illegitimate son with Walewska.

Napoleon’s romance with the beautiful Polish woman was the talk and gossip of all of Europe at the time. Dozens of books and many films were made about it. Notably, in the 1937 Hollywood production Madame Walewska, the role of Madame Walewska was played by the legendary film star Greta Garbo, at the height of her fame. Then, on December 10, 1812, Napoleon himself arrived incognito at the English Hotel on Wierzbowa Street in a modest sleigh carriage. Warsaw was experiencing a harsh winter, with chroniclers recording a temperature of -16°C that day. The severe frost was thwarting the plans for the conquest of Russia, as the Great Army was retreating from Moscow to France.

- We know quite a bit about Napoleon’s visit, as the memoirs of Tomasz Gąsiorowski, the then-owner of the English Hotel, have survived. This visit was connected to the retreat from the failed Russian campaign. Napoleon’s adjutant, Captain Count Wąsowicz of the Light Horse regiment, requested lodging for Duke Caulaincourt, as they did not want to officially announce the Emperor’s visit. Gąsiorowski initially refused, as hotels and restaurants were tired of hosting the light horsemen on unpaid credit, and French guests were notoriously demanding. On occasion, dishes they didn’t like were thrown out the window along with the plate. Despite his resistance, Gąsiorowski was persuaded by Count Wąsowicz to host the French guest. Since the temperature had dropped to -16°C, the rooms were heated, fortunately—because the mysterious guest turned out to be none other than Napoleon Bonaparte himself, says Rafał Bielski, founder of Skarpa Warszawska and a Warsaw historian.

Caulaincourt recalls that Napoleon was very pleased with his return to Warsaw. He declined the planned stay at the French Embassy and requested to be taken to the English Hotel, driving through Krakowskie Przedmieście. He even expressed a desire for a walk. “I’d like to be on this street again, as I once watched a splendid parade here.” The Emperor stepped out of the carriage, and Caulaincourt describes it: “(…) the Emperor’s magnificent velvet green cloak with gold embroidery caught the attention of a few humble passersby. They turned to look but didn’t stop, hurrying home to their fireplaces. He would have been hard to recognize anyway, as he wore a green hood, also of velvet, and a fur cap that covered half his face…”

Finally, a frozen Napoleon arrived at 11 a.m. at the English Hotel on Wierzbowa Street. “(…) he entered a small, low-ceilinged room where it was bitterly cold. A maid, kneeling, was blowing on the fire made of damp wood, which resisted her efforts, releasing more moisture into the chimney than warmth into the room…” (quote from Caulaincourt). Ambassador Dominique Pradt was called to the hotel and brought a bottle of fine Bordeaux, while hotel owner Tomasz Gąsiorowski, who remembered Napoleon from the Italian campaign, offered the house specialty for warmth—a homemade horseradish vodka. Napoleon, curious, savored the unknown taste for a moment, then drained the glass and exclaimed with delight: “By God! This is a true elixir that warms both the body and the mind! We needed this on the march to Moscow.”

Did the Emperor recall his orders from March 1807? “(…) those 300,000 rations of biscuits and those 18 or 20 thousand quarts of vodka that could be delivered to us within a few days will undo the plans of all the powers…” he wrote to Talleyrand, who was residing in Warsaw at the time—bishop, foreign minister, and later prime minister of France.

Before sitting down to the dinner prepared at the hotel, Napoleon summoned representatives of the Polish government and promised he would return to the Vistula in six months. As a parting gesture, he tipped Mr. Gąsiorowski ten Napoleons.

Bonaparte did not visit his beloved Maria on this occasion, but he had already ensured her and their son’s well-being. In 1812, after divorcing Chamberlain Walewski, Maria received estates in the Kingdom of Naples, including 69 farms, a palace in France, and a permanent pension. Less than a month after Napoleon’s visit to the English Hotel, on January 1, 1813, she left for Paris with her two sons, where she soon became friends with Napoleon’s first wife, Josephine. She later had secret meetings with Napoleon, even on the island of Elba, where he was in exile.

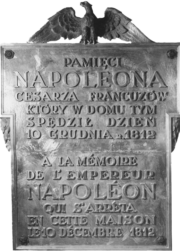

In memory of Napoleon’s stay at the English Hotel, a commemorative plaque was funded in the now-independent Polish Republic. For many years, it adorned the building’s façade until it was destroyed during World War II. Soon, a replica will be placed on the exterior of the Elixir restaurant at 9/11 Wierzbowa Street, near Teatralny Square in Warsaw. However, the plaque is not just a historical reminder but also an inspiration for a culinary and historical adventure.

The organizer of the “Bon Appetit Napoleon!” exhibition is the Vodka Museum, located on Wierzbowa Street near Teatralny Square, right next to the Elixir restaurant. For several years, it has been one of the more intriguing attractions on Warsaw’s tourist map. In addition to Napoleonic memorabilia, it houses a unique, world-class collection of artifacts related to the history of vodka. This world’s largest “vodka” collection, consisting of nearly 10,000 items, is presented through permanent and temporary exhibitions, as well as lectures, workshops, and educational programs.

“The Vodka Museum can serve as an inspiration to rediscover the culinary roots of our capital. Vodka, which originated on Polish soil, has been one of the most popular alcoholic beverages worldwide for over four centuries. It is also an important part of the history, traditions, and culture of the Polish table. Our mission is to document and showcase this phenomenon in all its richness and complexity,” says Piotr Popiński, Warsaw restaurateur, collector, and founder of the Vodka Museum.

This unique experience is divided into three stages. According to Piotr Popiński, this culinary-historical journey through time is best begun at the Vodka Museum, with a history lesson on the rise and fall of the Polish distilling industry before World War II, through the post-war era, the Polish People’s Republic, and the contemporary state of this vast market and industry.

The next step is a tasting at The Roots cocktail bar, where in addition to cocktails based on historical recipes dating back to the early 19th century, visitors can view unique items related to the history of bartending around the world.

“The culmination of this journey is a visit to the Elixir restaurant, where, in accordance with the principles of food pairing, modern Polish cuisine intertwines with centuries-old traditions of vodka, mead, and tincture production. Here we share fascinating stories, uncover a wealth of flavors, and even reveal the secret of what Napoleon ate and drank during his visit to Wierzbowa, including the horseradish vodka, which delighted the Emperor and is still produced today based on old recipes. This is how we offer a recipe for unforgettable memories from Warsaw, and our guests are pleasantly surprised by the unique experience,” concludes Piotr Popiński.

Napoleon was right! If only he had stayed on Wierzbowa one day longer…

From its very first year of operation, Elixir Restaurant has been regularly recognized in the Michelin Guide, The Roots cocktail bar was the first bar in Poland to be awarded by World 50 Best Discovery, and the Vodka Museum has been honored with the Teraz Polska emblem.”

The dishes for the Napoleonic-era menu were developed and reconstructed based on original recipes from the early 19th century, thanks to the courtesy of Professor Jarosław Dumanowski from the Culinary Heritage Center at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, and Grzegorz Mazur from the Historical Kitchen of the Museum of King Jan III’s Palace in Wilanów.

Historical information about Napoleon Bonaparte’s stay in Warsaw was provided by: Rafał Bielski, editor-in-chief of Skarpa Warszawska magazine; Jerzy Socal, writer, historian, and Varsavianist, co-author of the lifestyle portal Slow Poland; Igor Strumiński, historian, writer, publicist, and Warsaw tour guide; and Bartosz Paluszkiewicz, author of the blog Pre-War Restaurants, Bars, and Cafés.